Today's Geocuration is a quick one because of time constraints, but that doesn't mean it's lacking in interest.

Enjoy.

In my post The Art Machine: Andy Warhol's Pop Art, I talk about the motivation behind Warhol's iconic pop art. Another iconic pop artist that exhibited alongside Warhol was Roy Lichtenstein. While Andy Warhol turned art into a mass-produced non-art art machine, Lichtenstein worked to redefine the definition of art through parody. Chances are you've seen his work without realizing it (or maybe you did?).

If you look at the paintings' captions, you might notice the media used for these includes "magna." Magna was a brand name of acrylic resin paint that was developed in the late 1940s, and Lichtenstein used it extensively. It's different from traditional acrylic paint because the pigments are ground into acrylic resin by emulsifying them with solvents; it requires using turpentine or mineral spirits to work with because it, unlike traditional acrylic paint, is not water-soluble. Acrylic paint as we know it today was developed in 1960.

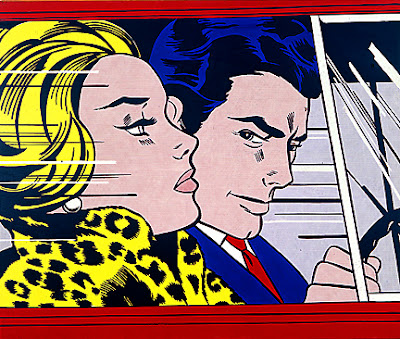

On the subject of painting media, you might also notice that he places strong emphasis on the primary colors: red, blue, and yellow. Lichtenstein worked off of old comic strips and popular advertising to produce works that are "not 'American' painting but actually industrial painting," a sentiment similar to Warhol's—a relatively unexplored sentiment in the 1960s.

Not only did Lichtenstein suggest commercialism, but his works remark on the idea of women being homemakers. These ideas live on presently in pop culture—take the Mad Men fad, for instance, and the revival in peplums and other 1950s-1960s fashions. Even the age-old damsel-in-distress is a theme repeated, albeit not originally Lichtenstein's idea; similarly, there has always been a special place in America's (and the world's) heart for thought and speech bubbles. Below you will find a quick look at how pop artist Roy Lichtenstein's work itself is parodied presently, similar to how he himself parodied other art.

Enjoy.

|

| In the Car by Roy Lichtenstein (American); 1963; oil and magna. Location: Edinburgh, Scotland; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. |

|

In my post The Art Machine: Andy Warhol's Pop Art, I talk about the motivation behind Warhol's iconic pop art. Another iconic pop artist that exhibited alongside Warhol was Roy Lichtenstein. While Andy Warhol turned art into a mass-produced non-art art machine, Lichtenstein worked to redefine the definition of art through parody. Chances are you've seen his work without realizing it (or maybe you did?).

If you look at the paintings' captions, you might notice the media used for these includes "magna." Magna was a brand name of acrylic resin paint that was developed in the late 1940s, and Lichtenstein used it extensively. It's different from traditional acrylic paint because the pigments are ground into acrylic resin by emulsifying them with solvents; it requires using turpentine or mineral spirits to work with because it, unlike traditional acrylic paint, is not water-soluble. Acrylic paint as we know it today was developed in 1960.

|

| I know...Brad by Roy Lichtenstein (American); 1964; oil and magna. Location: Cologne, Germany; Wallraf-Richartz Museum. |

|

On the subject of painting media, you might also notice that he places strong emphasis on the primary colors: red, blue, and yellow. Lichtenstein worked off of old comic strips and popular advertising to produce works that are "not 'American' painting but actually industrial painting," a sentiment similar to Warhol's—a relatively unexplored sentiment in the 1960s.

Not only did Lichtenstein suggest commercialism, but his works remark on the idea of women being homemakers. These ideas live on presently in pop culture—take the Mad Men fad, for instance, and the revival in peplums and other 1950s-1960s fashions. Even the age-old damsel-in-distress is a theme repeated, albeit not originally Lichtenstein's idea; similarly, there has always been a special place in America's (and the world's) heart for thought and speech bubbles. Below you will find a quick look at how pop artist Roy Lichtenstein's work itself is parodied presently, similar to how he himself parodied other art.

|

| M.A.C. Makeup Artist Karin Stone's Lichtenstein Girl via Adriana de Barros's article, "The Real life Lichtenstein-Comic-Girl" |

|

| Chelsea King's Roy Lichtenstein Nails via Chelsea King's Get Nailed Follow Chelsea on Twitter |